The Influenza Pandemic of 1918: Philadelphia

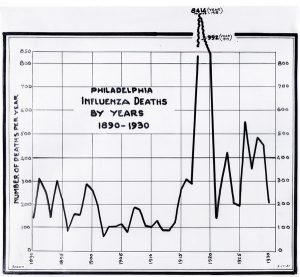

Influenza tore through Philadelphia at a ferocious pace in October and early November. During the second week of October 2,600 people succumbed to the flu, and the following week saw that number nearly double.The devastating effects of the virus, known today as H1N1, were first felt in late summer 1918 along the eastern seaboard in a military encampment outside of Boston. From there, influenza propagated ruthlessly across the country, claiming nearly 700,000 lives before running its course in the spring and summer of 1919.

For an instant in the fall of 1918 it was as if Philadelphia had been transported back to the fourteenth century to that grisly time when victims stricken with plague were often found dead within twenty four hours of contracting it. Perhaps the words of the renowned cardiologist Isaac Starr, a third-year medical student at the University of Pennsylvania at the time of the outbreak, came closest to encapsulating the ordeal of late 1918 when he noted simply that it was as if “the life of the city had almost stopped.

With hospitals inundated and facing a shortage of medical staff, volunteers were culled from religious organizations, civic associations, and, most prominently, the city’s medical and nursing schools. Across Philadelphia these men and women turned parish houses and armories into temporary emergency hospitals, but on the whole extra assistance remained scarce. As one volunteer recalled, “if you asked a neighbor for help, they wouldn’t do so because they weren’t taking any chances…It was a horror-stricken time.” And yet just as quickly did the horror arrive did it also depart. When 10,000 dosages of a flu vaccine finally arrived in Philadelphia on October 19, the virus was already in the beginning stages of a rapid decline. By the second week of November, deaths caused by influenza and pneumonia were less than a quarter of what they were the week prior, and by the end of the month the death toll had dipped under 100 for the week for the first time since early September. Still, the city’s death rate from influenza, at approximately 407 per 100,000 people, exceeded that of all other American cities in 1918.

In October 1918, Philadelphians had little time for public health; there was a fundraising parade to put on. Citizens had been ordered to do their share and buy half a billion dollars’ worth of Liberty Bonds in support of the war effort, and to do so before the end of October. No way would this be possible in a city scared and shuttered. On September 28th the parade on Broad Street took place as scheduled; 200,000 turned out for it.

Symptoms of this strain of influenza began as soon as a day after exposure. On September 30th and October 1st the city hospitals found 466 new cases on their hands. Twenty-four hours later, on October 2nd, the Inquirer reported an additional 635 cases.

“Within seventy-two hours after the parade” writes John Barry, in The Great Influenza,“every single bed in each of the city’s thirty-one hospitals was filled. And people began dying. Hospitals began refusing to accept patients. … On October 3, only five days after Krusen had let the parade proceed, he banned all public meetings in the city-including, finally, further Liberty Loan gatherings—and closed all churches, schools, theatres. Even public funerals were prohibited.”

As World War I drew to a close in November 1918, the influenza virus that took the lives of an estimated 50 million people worldwide in 1918 and 1919 began its deadly ascent. The United States had faced flu pandemic before, in 1889-90 for example, but the 1918 strain represented an altogether new and aggressive mutation that proved unusually resistant to human attempts to curb its lethality. The devastating effects of the virus, known today as H1N1, were first felt in late summer 1918 along the eastern seaboard in a military encampment outside of Boston. From there, influenza propagated ruthlessly across the country, claiming nearly 700,000 lives before running its course in the spring and summer of 1919.

While the country celebrated the end of World War I, the onset of the influenza virus would take the lives of 50 million people over the course of the year worldwide; 12,200 succumbed to the virus and its complications in Philadelphia alone. In October and November hospitals were overrun and were faced with a shortage of medical staff and volunteers; throughout the city men and women turned parishes, armories, garages and any empty space into emergency hospitals. By the middle of November, deaths from the influenza virus had dropped significantly from the week before and continued to fall. Although the Influenza claimed thousands of lives throughout the country, Philadelphia suffered the greatest losses at approximately 407 per 100,000 people.

Between October and November of 1918 thousands were sick and dying from what was coined the “Spanish Influenza” and the city all but shut down.The influenza came as quickly as it went; vaccines arrived to Philadelphia on October 19th and by that time the disease already started to slow down.